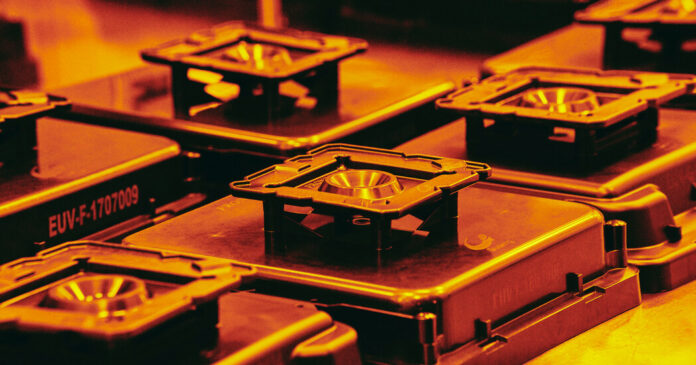

They are sleek white boxes about the size of large vans, and they are now at the center of the US-Chinese technology conflict.

As the United States tries to slow China’s progress toward technological advances that could help its military, the complex lithography machines that print intricate circuits onto computer chips have become a major bottleneck.

The machines are central to China’s efforts to build its own chip manufacturing industry, but China does not yet have the technology to make them, at least not in their most advanced forms. This week, U.S. officials took steps to curb China’s progress toward that goal by banning companies worldwide from sending more types of chip-making machines to China unless they receive a special license from the U.S. government.

The move could be a major blow to China’s chip manufacturing ambitions. It is also an unusual expansion of American regulatory power. American officials took the position that they could regulate devices made outside the United States if they contained even a single U.S.-made part.

The decision gives U.S. officials new influence over companies in the Netherlands and Japan, where some of the most advanced chip machines are made. In particular, U.S. regulations will now stop shipments of some machines that use deep ultraviolet, or DUV, technology, manufactured primarily by Dutch firm ASML, which dominates the lithography market.

Vera Kranenburg, a China researcher at the Clingendael Institute, a Dutch think tank, said that while ASML has made it clear that it will follow the regulations, the company has already suffered from previous regulations that prevented it from exporting a more sophisticated lithography machine to China prohibited.

“Of course they are not happy about the export controls,” she said.

After being pushed into geopolitics again, ASML responded cautiously, saying in a statement this week that it complies with all laws and regulations in the countries where it operates. Peter Wennink, chief executive, said the company was unable to supply certain tools to “only a handful” of Chinese chip factories. But “it’s still revenue that we had in 2023 that we won’t have in 2024,” he added.

In a statement, Dutch Foreign Trade Minister Liesje Schreinemacher said that the Netherlands shared U.S. security concerns and continually exchanged information with the United States, but that “ultimately each country decides for itself what export restrictions to impose.” She pointed to looser restrictions announced by the Dutch government in June.

A spokesman for the US Commerce Department declined to comment.

ASML’s technology has enabled leaps in global computing power. The increasing precision of its machines — which consist of tens of thousands of components and cost up to hundreds of millions of dollars each — has led to the circuitry on chips becoming ever smaller, allowing companies to pack more computing power into a tiny piece of silicon.

Technology has also given the United States and its allies an important leverage over China as governments compete to turn technological advances into military advantages. Although Beijing is pouring money into the semiconductor industry, Chinese chipmaking equipment has lagged many years behind the performance of ASML and other major machinery suppliers, including Applied Materials and Lam Research in the United States and Tokyo Electron and Canon in Japan.

But U.S. efforts to weaponize this technological advantage against China appear to be straining alliances. In Europe, government officials increasingly agree with the United States that China poses a geopolitical and economic threat. But they still have concerns about undercutting their own companies by denying them access to China, one of the world’s largest and most dynamic technology markets.

Dutch technology in particular was the focus of a multi-year pressure campaign by the United States. In 2019, the Trump administration persuaded the Dutch to block shipments to China of ASML’s most advanced machine, which uses extreme ultraviolet technology.

After months of diplomatic pressure from the Biden administration, the governments of the Netherlands and Japan agreed in January that they would also independently restrict sales of some deep ultraviolet lithography machines and other types of advanced chip-making equipment to China.

The United States and its allies view the sale of the deep ultraviolet lithography machines as less of a national security risk. The chips they make are significantly less advanced than those made with the most advanced machines that power the latest smartphones, supercomputers, and AI models today.

But that position was tested this summer when a Chinese company used ASML’s deep ultraviolet lithography technology along with other advanced machines to overcome a technological barrier that U.S. officials had hoped China would face would stop you from reaching them.

In August, Chinese telecom giant Huawei unexpectedly released a new smartphone with a Chinese-made chip with transistor dimensions of seven nanometers, just a few technology generations behind the latest Taiwan-made chips. Analysts have concluded that China’s Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation manufactured the chip using Dutch deep ultraviolet lithography machines.

Gregory C. Allen, a technology expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank, said the new export control rules had been in the works long before Huawei’s announcement. However, he said the development “helped leaders across the U.S. government understand that there was no more time to lose and that updated controls are urgently needed.”

Mr. Allen said the controls wouldn’t necessarily doom China’s most advanced chipmakers immediately because they already have plenty of advanced machines in stock. But it would “dramatically limit” their ability to make the most advanced types of semiconductors, such as seven-nanometer chips, he said.

Currently, ASML continues to do good business with China. In its earnings report this week, ASML said sales to China surged in the third quarter, accounting for 46 percent of the company’s total global sales, well above historical levels.

Analysts at TD Cowen estimated that ASML’s China sales would reach 5.5 billion euros (about $5.8 billion) this year, more than double its total sales last year. Next year, the new export controls could cut the company’s revenue in China by 10 to 15 percent, they predicted.

Roger Dassen, ASML’s chief financial officer, said on the earnings call that most of the orders ASML processed this year were placed in 2022 or even the year before and were largely for machines that make slightly older types of chips would.

All deliveries were “largely within the export regulations,” said Dassen.

For the machines subject to new US restrictions, the Dutch company is now banned from supplying spare parts and helping to maintain these systems. This means that Chinese companies will likely have problems with production at some point.

These hugely expensive machines rely on regular software and maintenance support to keep producing chips, said Joanne Chiao, a semiconductor analyst at TrendForce, a market research firm.

ASML is not the only equipment supplier affected by the latest restrictions. Other types of advanced machines essential to making the most advanced chips, such as those made by U.S. companies Applied Materials and Lam Research, are detailed in the latest restrictions.

In a conference call on Wednesday, Lam said sales in China rose 48 percent in the fiscal first quarter as companies stocked up on machinery to make both sophisticated chips and advanced products. It was already estimated that restrictions on sales to China would depress sales by $2 billion this year; Executives added that the expanded rules issued this week would not significantly change that estimate.

An Applied Materials spokesman said the company was still reviewing the new rules to assess their potential impact.

John Liu contributed reporting from Seoul.