Despite high interest rates, real estate prices have held up better than expected. But that does not mean that the real estate market is healthy.

When the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates in 2022, most economists thought the housing market would be the first to suffer: Higher borrowing costs would make buying and building more expensive, leading to lower demand, less construction activity, and lower prices.

They were right — at first. Construction slowed, but then picked up again. Prices stalled, but then started to rise again. Higher interest rates made it harder to afford a home, but Americans still wanted to buy.

The result is a housing market that is different and stranger than the one described in economics textbooks. Parts of it have proven surprisingly resilient. Other parts are almost completely locked up. And some seem to be on the brink, threatening to collapse if interest rates stay high for too long or the economy unexpectedly weakens.

It is also a market of stark contrasts. People who secured low interest rates before 2022 were, in most cases, able to see their home values rise rapidly while remaining protected from higher borrowing costs. Those who did not yet own their own home, on the other hand, often had to choose between unaffordable rents and unaffordable house prices.

But the situation is complex. In some parts of the country, homeowners are facing exploding insurance costs. In some cities, rents have fallen. Developers are finding ways to make new homes affordable for first-time buyers.

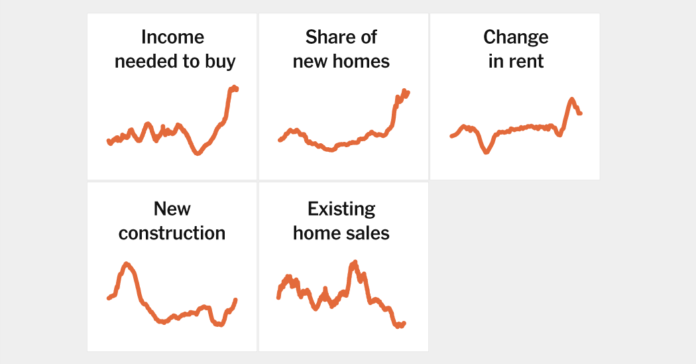

No single indicator tells the whole picture. Rather, economists and industry experts say that to understand the housing market, you need to look at a range of data that sheds light on different pieces of the puzzle.

1. It's hard to find a house to buy.

The rapid rise in interest rates depressed demand for homes because it made lending more expensive. But it also led to a sharp decline in supply: many owners are holding on to their homes longer than they otherwise would because they would have to forego the extremely low interest rates if they were to sell.

This “rate lock” phenomenon has led to a severe shortage of homes for sale. It’s not the only factor: Home construction had been stagnating for years before the pandemic, and retiring baby boomers were choosing to stay in their homes rather than moving into senior living communities or smaller condos, as many housing experts had expected.

Many economists argue that the lack of supply has helped keep prices high, especially in some markets. However, they disagree on the magnitude of this impact. What is certain, however, is that it is extremely difficult for anyone who wants to buy a home to find one.

2. Houses are unaffordable.

Already high home prices have soared during the pandemic, rising more than 40 percent nationwide from late 2019 to mid-2021, according to the S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller price index. They have risen more slowly since then, but they have not fallen as many economists expected when the Fed began raising interest rates.

Rising interest rates have made those prices even more unaffordable for many buyers. Someone buying a $300,000 home with a 10 percent down payment could expect a mortgage payment of about $1,100 a month at the end of 2021, when interest rates on a 30-year fixed-rate loan were about 3 percent. Today, with interest rates at about 7 percent, the same home would cost about $1,800 a month, an increase in monthly costs of about 60 percent. (That doesn't even take into account the rising cost of insurance or other expenses.)

Economists measure affordability in different ways, but they all show pretty much the same thing: Buying a home, especially for first-time buyers, is more unaffordable than at any time in decades, or perhaps ever. An index from Zillow shows that a typical household buying the average home with a 10 percent down payment can expect to spend more than 40 percent of its income on housing costs, well above the 30 percent that financial experts recommend. And in many cities like Denver, Austin and Nashville — not to mention longtime outliers like New York and San Francisco — the numbers are much worse.

3. New houses fill (part of) the gap.

Perhaps the most surprising development in the real estate market over the past two years has been the resilience of new home sales.

Rising interest rates usually cause problems for property developers because the high borrowing costs drive away buyers and make construction itself more expensive.

But this time, with so few existing homes for sale, many buyers have turned to new construction. At the same time, many large builders have been able to borrow when interest rates are low and use that financial firepower to lower interest rates for their customers – making their homes more affordable without having to cut prices.

As a result, new home sales have remained relatively stable even as existing home sales have plummeted. Developers have tried particularly to appeal to first-time buyers by building smaller homes, a market segment they had virtually ignored for years.

It's unclear how long that trend can continue, though. Many builders scaled back activity when interest rates first rose, meaning fewer new homes will come on the market in the coming years. And if interest rates stay high, builders may find it harder to offer the financial incentives they use to attract first-time buyers. Private developers began building new homes in May, the slowest pace in nearly four years, the Commerce Department said Thursday.

4. The rents are also unaffordable.

During the pandemic, rents skyrocketed across much of the country as Americans fled cities and searched for housing. Then they continued to rise as the strong job market boosted demand.

Rising rents contributed to a housing boom that created an oversupply of supply on the market, particularly in southern cities like Austin and Atlanta. This caused rents to rise more slowly or even fall in some places.

But this reticence has been slow to trickle down to the market. Many tenants are paying rents negotiated earlier in the housing cycle, and new construction is focused on the luxury market, which doesn't do much good for middle- and low-income renters, at least in the short term.

All of this has led to a worsening crisis of rent insecurity. A record share of renters spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing, Harvard's Joint Center for Housing Studies recently found, and more than 12 million households spend more than half their income on rent. Rent is no longer just a problem for the poor: The Harvard report found that rent is becoming a burden even for many households earning more than $75,000 a year.

5. There may be a postponement.

For the past two years, the real estate market – especially for existing homes – has been at a dead end. Buyers can't afford homes unless prices or interest rates fall. Owners feel little pressure to sell and aren't eager to become buyers.

What could break the deadlock? One possibility is lower interest rates, which could bring a flood of buyers and sellers back into the market. But with inflation proving stubborn, rate cuts do not seem imminent.

Another possibility would be a more gradual return to normality as owners conclude they can no longer delay a move and are more willing to make a deal, and as buyers come to terms with higher interest rates.

There are signs that this may be the case. More and more owners are putting their homes up for sale, and more are lowering prices to attract buyers. Builders are completing more and more new homes without finding a buyer. Real estate agents are telling of empty homes and homes that have been on the market longer than expected.

Few are expecting prices to drop. Millennials are in the peak home-buying phase, meaning demand for homes should be high. And because of years of under-construction, the country still has too few homes by most standards. And because most homeowners have plenty of equity and lending standards are tight, there probably won't be a wave of forced sales like when the housing bubble burst nearly two decades ago.

But that also means the affordability crisis is unlikely to resolve itself anytime soon. Lower interest rates would help, but it will take more than that to make it possible for many young Americans to afford a home.