The American labor market could shift into lower gear this spring, a turnaround that economists have been anticipating for months following a strong recovery from the pandemic shock.

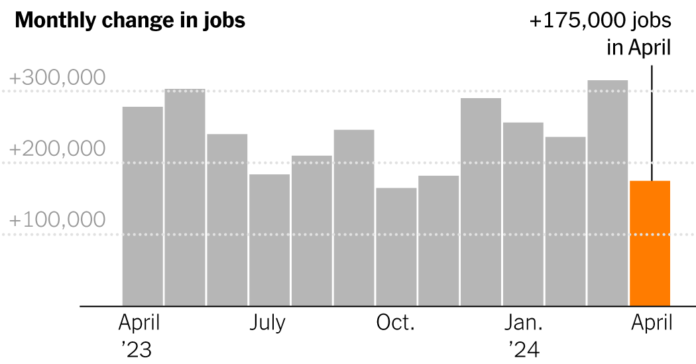

As the Labor Department reported on Friday, employers added 175,000 jobs in April, falling short of forecasts. The unemployment rate rose to 3.9 percent.

A slower expansion, past the 12-month average of 242,000 jobs, isn't necessarily bad news given that layoffs have remained low and most sectors appear stable.

“It’s not a bad economy; It’s still a healthy economy,” said Perc Pineda, chief economist at the Plastics Industry Association. “I think it’s part of the cycle. Given the limits of our economy, we cannot continue robust growth indefinitely.”

The labor market has been defying forecasts of a significant slowdown for more than a year amid rapid escalation in borrowing costs, a minor banking crisis and two major wars. But economic growth fell sharply in the first quarter, suggesting that the exuberance of the past two years may be settling into a more sustainable rhythm.

Wage growth slowed, with average hourly wages rising 3.9 percent year over year, compared to 4.1 percent in the March report. The rapid wage growth in the first quarter, reflected in a higher-than-expected employment cost index, may be due in part to the wage increases and minimum wage increases that took effect in January, as well as new union contracts.

The number of hours worked per week has fallen, another sign that employers need fewer staff. A broader measure of unemployment that includes people working part-time for economic reasons rose to 7.4 percent from record lows in late 2022.

The results could be welcome news for the Federal Reserve, which has kept interest rates steady as inflation has remained stubborn. Although Fed Chairman Jerome H. Powell said this week that he was not seeking lower wage growth, he added that sustained, hot wage increases could prevent inflation from easing.

Bond yields fell on the new data, suggesting expectations the Fed could cut interest rates this year after some doubts about it, and stocks rallied.

President Biden hailed the report as a continuation of the “Great American Comeback,” but his presumptive rival in November's election, former President Donald J. Trump, called it “TERRIBLE JOB NUMBERS” on his Truth Social platform. Under Mr. Trump's presidency, before the pandemic hit in March 2020, monthly job gains averaged about 180,000 — just a little more than April's gain.

The April figure is in line with other indicators of worsening conditions, which have increased in recent months: the number of job vacancies has fallen significantly since its peak two years ago, and the number of workers leaving their jobs, is lower than before the pandemic. And February and March hiring numbers, which came in higher than forecast, may have been flattered by an unusually warm winter.

“We have seen a significant decline in labor demand and it is no surprise that in this economic environment where interest rates are still elevated, hiring is also slowing,” said Lydia Boussour, senior economist at consultancy EY-Parthenon.

Job growth has been limited to a few industries, and that trend continued in April's seasonally adjusted numbers, with healthcare – which is driven by aging demographics and does not fluctuate as much with economic cycles – accounting for a third of the growth.

Leisure and hospitality employment increased only slightly, halting fairly rapid growth as the industry approaches its pre-pandemic workforce levels.

The impact of higher interest rates is clearly visible in manufacturing, a capital-intensive sector where employment has been essentially stagnant since late 2022. Federal incentives for the production of semiconductors and clean energy equipment are driving investment, but the impact on employment has been muted.

That's true for Voith Hydro in York, Pennsylvania, a manufacturer of machinery for dams and pumped-storage systems that provide a way to manage electricity demand. Some contracts were accelerated through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and a tax break in the Inflation Reduction Act recently supported the installation of new equipment.

While Voith signed a new contract with its unionized workers last year that provided better wages and benefits to remain competitive with nearby employers, its workforce of 350 employees has not grown significantly.

“There are fewer people getting into the trade and there is a smaller pool of people to choose from,” said Carl Atkinson, vice president of sales and marketing for the hydro division. “It just presents a whole group of manufacturers with the challenge of being more efficient.”

This strategy has contributed to strong productivity growth in recent quarters, which has helped wages rise faster than prices. Depending on how many people start looking for work, such efficiencies could also cause the unemployment rate to rise. So far, however, labor supply has been a key factor in the surprisingly strong job growth of the last two years.

Part of that is due to the increasing influx of legal and illegal immigrants, which Goldman Sachs calculates added about 80,000 workers a month to the labor force last year and will add another 50,000 a month this year. Economists at the Brookings Institution estimated that immigration could create 160,000 to 200,000 jobs per month in 2024 without fueling inflation.

But labor availability was also boosted by women ages 25 to 54 – widely considered to be in their prime working years – setting a labor force participation record of 78 percent in April.

Among those back on the job market this year is Juliette Gore, 46, who worked in sales for credit reporting company Equifax before taking time off to raise her three sons. She then started a computer networking equipment company with her husband in suburban Atlanta, but sold her stake when they divorced in 2022.

After spending a year renovating her home, Ms. Gore began job hunting in early 2024. This proved to be bad timing as service sector employers had pulled back after a period of rapid hiring. She sent out dozens of applications but only got two interviews, and the closest thing to a job offer paid far less than she would have expected.

“I have a feeling it’s going to take a lot longer than I expected,” Ms. Gore said. “Some say things won’t improve until early next year.”

Declining job availability may also lead some people to turn to jobs that don't show up in the monthly employer survey. The share of accounts with app-based revenue hit a record high in the first three months of this year, mostly from ride-sharing revenue, according to an analysis of Bank of America's own data.

A rising unemployment rate could slow consumer spending, which, while also depleting the bank balances built up during the pandemic, still leaves behind a fundamentally healthy economy.

“We're still forecasting what we would call a slight slowdown, but we see the picture improving again,” said Stephen Brown, deputy chief economist for North America at Capital Economics. “For the average worker, it won’t feel like a slowdown.”