A Catholic archbishop has filed a lawsuit against Canada's physician-assisted dying law, which includes both medically assisted suicide and euthanasia. The case could have far-reaching implications for religious freedom, conscience rights, property rights and public-private partnerships.

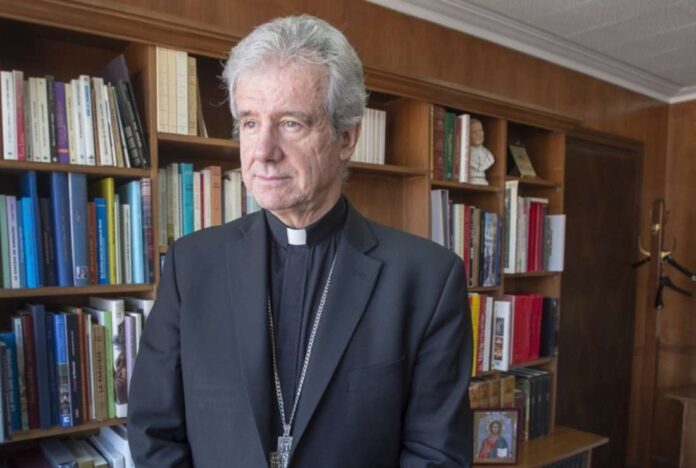

Archbishop Christian Lépine of Montreal appealed to the Quebec Supreme Court on February 5, asking for an immediate suspension of the application of a June 2023 amendment to Canada's end-of-life care law.

The amendment states that palliative hospices cannot exclude euthanasia from the care they offer.

Since 2016, Canada's Medical Assisted Dying Act (MAID) exempts doctors and nurses from criminal charges who, at their own request, administer or prescribe medication to cause a person's death. The law contains protocols to ensure that a patient requesting MAID is fully informed and consents voluntarily.

Archbishop Lépine particularly wants to protect the St. Raphael Palliative Care Home and Day Center in Montreal, a 12-bed non-profit facility that provides free care regardless of ethnicity, social status, religious beliefs, sexual orientation or gender identity.

The Catholic Register, Canada's national Catholic newspaper based in Toronto, reported that after the closure of St. Raphael the Archangel Parish, the Archdiocese of Montreal transferred the building and land to Maison St-Raphael, a community organization created to… Home to run, under a 75 year lease. It required that the facility — which opened in 2019 — never administer MAID.

On its website, St. Raphael explains that the palliative care approach supports life and views death as a natural part of life, and that the center's mission aims to relieve physical, psychological and spiritual suffering and improve patients' quality of life as well those of their loved ones. The aim is to offer a path to the end of life with compassion and humanity, while respecting the needs and boundaries of every person.

That mission is not possible under the amendment, the archdiocese's lawsuit says, noting that from the start, St. Raphael had an agreement with Montreal's Health and Human Services Department acknowledging that St. Raphael did not provide MAID, but had established protocols for transferring a patient who requested it to be removed from her care.

The Catholic Register reported that Quebec Health Minister Sonia Bélanger in November rejected St. Raphael's request for an exemption from MAID requirements, calling MAID part of the continuum of palliative and end-of-life care available at all facilities Must be made available to provide end-of-life care and lifelong care at the patient's request.

According to The Catholic Register, the change also puts property rights at stake in the archdiocese's lawsuit: St. Raphael is a private institution that is free to decide its direction, policies and approach, even if it receives public funding, otherwise it is In fact, it was about the state appropriating a religious building for MAID. The lawsuit also alleges that the change can cripple religious groups' efforts to serve society if their sincere beliefs and convictions cannot be respected.

In a Feb. 6 statement posted on its website, the Archdiocese of Montreal said: “The Catholic Church recognizes the need for quality palliative care that preserves the dignity of human life by providing effective pain management while responding to the “addresses the emotional, affective and spiritual needs” of individuals.

According to Catholic teaching, human life is considered sacred and inviolable, extending from conception to natural death, the archdiocese said. Palliative care accompanies individuals and their families through the end-of-life process with the goal of relieving pain without prolonging or hastening death.

In contrast, MAID results in the individual's premature death, the archdiocese said. Therefore, the Catholic Church considers euthanasia to be an act of euthanasia and considers it morally unacceptable as a response to the suffering and distress that people experience at the end of their lives.

Archbishop Lépine told The Catholic Register that the case is not only an issue of palliative care, but also an issue of freedom of conscience.

We talk about palliative care and MAiD because the law revolves around these issues. But it is actually about freedom of conscience, not only for individuals but also for institutions, said the archbishop. That is what we want to promote. Whoever we are, we need a society in which there is freedom of conscience for people and institutions.