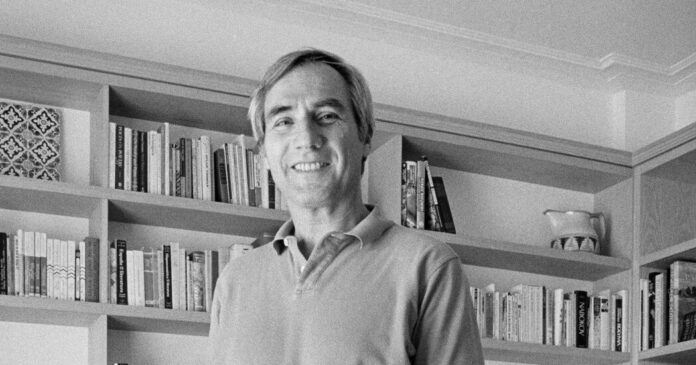

Bernard Marson, the architect and developer who played a prominent role in transforming an industrial district in Lower Manhattan into SoHo, an affordable neighborhood for artists to work and live in before it blossomed into an enclave of chic boutiques, celebrity bars and overpriced apartments, died July 9 at his home in Los Angeles. He was 91.

His death was confirmed by his son Alexander.

“Mr. Marson was almost single-handedly responsible for growing New York City’s SoHo into an artist community and historic district,” said Raquel Ramati, who led the Urban Design Group in Mayor John V. Lindsay’s administration, recommending him for a fellowship at the American Institute of Architects.

Mr. Marson was already a prominent architect in the late 1970s when he encountered the South Houston Industrial District, a 50-block area of five- and six-story buildings, many with elegant 19th-century cast-iron facades. The borough had just escaped the wrecking ball when Robert Moses’ plans for a Lower Manhattan Expressway were canceled.

The neighborhood was in transition, ripe for the kind of project that Mr. Marson had undertaken with Israeli architect Moshe Safdie in Jerusalem: the renovation of Western Wall Square and the Jewish Quarter in the Old City in 1974-1976.

In Manhattan, many tenants between Houston and Canal Streets, mostly small businesses — yarn and paper jobbers, rag converters, blinds and corrugated board makers, and garment sweatshops — moved to places with lower taxes and labor costs, leaving behind a dwindling industrial base that city officials were desperate to preserve .

These shops were replaced by a burgeoning artists’ colony in the area south of Houston Street, which had already been informally called SoHo. Artists converted high, undivided loft areas into studios and living quarters – a violation of city ordinances in a zone designated for industrial use.

In the late 1970’s, when the city was in an economic doldrums, Mr. Marson was at the forefront of adapting several former manufacturing buildings to create an entirely new neighborhood.

Along with other investors, he bought architect Ernest Flagg’s 12-story Little Singer Building and four other buildings, including a former glue factory.

Some of the space was already being used illegally by artists, but Mr. Marson spotted a loophole in what most city officials believed to be a ironclad ban — an obscure zoning that allowed “studios with annexes” in manufacturing neighborhoods. To the dismay of officials, the city’s Board of Standards and Appeals directed the building authority to permit Mr. Marson to proceed.

What followed was a protracted legal and administrative dispute. On one side were city officials and some landlords trying to enforce the zoning law to protect existing tenants and prevent gentrification; On the other hand, with Mr. Marson at the helm, developers and artist groups argued for divergent zoning to reflect the new realities of the real estate market.

In some cases, landlords and developers took advantage of tenants who had improved the properties at their own expense by raising rents (and tenant hackles) even though they were still illegally occupied. But the proliferation of manufacturing-to-residential conversions in SoHo and surrounding neighborhoods eventually led to new regulations, the establishment of the Loft Board, and the approval of many of the lofts already occupied.

“It basically legalized what was already happening,” said Peter Samton, an architect and a former colleague of Mr. Marson. “The unique aspects of his contributions were the fusion of architecture and development that was so unusual back then, some 50 years ago.”

In 1982, state legislatures passed legislation that would protect 90 percent of loft tenants, including those in large loft neighborhoods like SoHo, Tribeca, and NoHo in lower Manhattan, according to Carl Weisbrod, director of the New York City Office of Loft Enforcement.

Anthony Schirripa, who was president of the New York chapter of the American Institute of Architects in 2010, described Mr. Marson at the time as “a key player in SoHo’s transformation from its sweatshop past to its jewel-like present.”

Recent recorded neighborhood sales included a two-bedroom apartment at 561 Broadway for $4 million and a one-bedroom apartment at 242 Lafayette Street for $2 million.

Bernard Aaron Marson was born on March 21, 1931 in Manhattan to Alexander Marson, an immigrant from Russia who became a paint salesman, and Etta (Germaine) Marson, who worked in a Harlem store. He grew up in the West Bronx.

In 1951, after graduating from DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, he earned a degree in civil engineering from the College of Engineering at New York University. During the Korean War he served as a nuclear weapons officer.

After receiving an architecture degree from Cooper Union in 1961, he worked with Marcel Breuer as that architect’s site representative on the construction of the Whitney Museum of American Art on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, a Brutalist building that now temporarily houses the Frick Collection while the Frick Museum nearby is being renovated.

In his own practice, Mr. Marson was notably commissioned to renovate the 1920’s Montauk Manor, the Tudor Revival Hotel on Long Island’s East End designed by Schultz and Weaver and built by Carl G. Fisher who developed Miami Beach , when the hotel was converted to condominiums in the 1970s.

He married Ellen Sue Engelson in 1978. Alongside her son, she survives him along with her daughter Eve; and two grandchildren. In 2017, the couple moved to California.