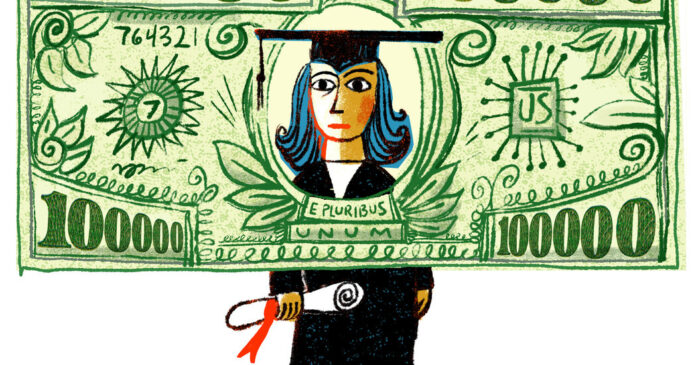

It was only a matter of time before a college would have the courage to list its cost of attendance at nearly $100,000 per year. We'll get our first glimpse of it this spring.

A letter to a newly admitted engineering student at Vanderbilt University listed a total price – room, board, personal expenses, a powerful laptop – at $98,426. A student who travels from the Nashville campus home to Los Angeles or London three times during the year could make six figures.

This eye-popping sum is an anomaly. Only a tiny fraction of students attending college will pay anywhere near that much any time soon, and about 35 percent of Vanderbilt students—those who do not receive need-based or merit-based aid—pay full list price.

But a few dozen other colleges and universities that reject the vast majority of applicants are likely to reach that threshold within a few years. Her willingness to cross that line raises two questions for anyone deciding to pursue a degree: How did it come about, and can it possibly be worth it?

Who pays what?

According to the College Board, the average list price for tuition, fees, room and board in 2023-24 at private, nonprofit four-year schools was $56,190. At public four-year colleges, in-state students had to pay an average sticker price of $24,030.

However, that's not what many people pay, not even close. According to federal data that the College Board used in a 2023 report, in the 2019–20 school year, 39 percent of in-state students attending two-year colleges full-time received enough grants to cover their entire tuition and fees (but did not their cost of living, which can make attending school extremely difficult). At public four-year schools, 31 percent paid nothing for tuition and fees, while 18 percent of students at private colleges and universities qualified for the same offering.

These private colleges continue to offer significant discounts to people of all income levels. A study by the National Association of College and University Business Officers found that private nonprofit colleges and universities reduced their tuition by 56 percent compared to normal rates in the 2022-23 school year.

Vanderbilt also offers discounts and financial aid is extremely generous. This year it was announced that families with incomes of $150,000 or less would pay no tuition in most cases.

Yet more than 2,000 students there who don't receive need-based or merit-based aid will soon pay $100,000 or more. Why does Vanderbilt need so much money?

Where the money goes

At some small liberal arts colleges with enormous endowments, schools say even $100,000 wouldn't cover the average cost of educating a student. Williams College, for example, says it spends about $50,000 more per student than list price.

In other words: everyone receives a subsidy. Maybe the list price should be over $100,000 so that the foundation doesn't provide unnecessary help to wealthy families. Or perhaps such a high price would deter low-income applicants who don't know they might get a free ride there.

According to Vanderbilt, the per-student expense is $119,000. “The gap between the award and cost of attendance is funded by our endowment and the generous philanthropy of donors and alumni,” Brett Sweet, vice chancellor for finance, said in an emailed statement.

No one at school would meet with me to break down that number or call to talk about it. But Vanderbilt's financial reports provide clues about how the company spends its money. In fiscal year 2023, 52 percent of operating expenses went to salaries and wages for faculty, staff and students, as well as fringe benefits.

Robert B. Archibald and David H. Feldman, two academics who wrote “Why Does College Cost So Much?”, explained in their book why labor costs at these institutions are so sensitive.

“The key factors are that higher education is a personal service, that it has not experienced large labor-saving productivity gains, and that the wages of the highly skilled workers who are so important at colleges and universities have skyrocketed,” they said. “These are macroeconomic factors. They have little to do with any pathology in higher education.”

Critics of the industry still believe there has been a kind of administrative bloat that is driving up tuition and inflating salaries. But what exactly is flatulence?

The administration monitors compliance, such as laws allowing disabled people access to and through the university and preventing schools from discriminating against women. If we don't like a regulation, we can vote for different legislators.

Likewise, in a free market, families can make alternative choices if they need fewer mental health professionals and their supervisors, computer network administrators, academic advisors, or career counselors. And yet, the first (pre-vetted) question Vanderbilt Chancellor Daniel Diermeier answered at Family Weekend last fall was whether Vanderbilt should invest even more in career counseling after the school dropped five spots in the annual U.S. News rankings.

Is it worth it?

Even though many families aren't lining up for affordable residential basic training, they're still asking a lot of good questions about the value. So is a $400,000 college education ever worth it?

It depends, and you knew the answer was coming, right?

Most prospective students wonder what their income is, and you can use the federal government's College Scorecard website to search for bachelor's degree programs. This program-level data is available for alumni four years away from graduation, but only for those who received federal financial aid.

Vanderbilt's biomedical/medical engineering majors earn an average of $94,340 in four years. English language and literature majors earn $53,767.

These are good results, but are they unique to Vanderbilt? “At a flagship state university, you could get an engineering degree that’s just as valuable as something you’d get at Vanderbilt,” said Julian Treves, a financial advisor and higher education specialist whose newsletter informed me about what’s going on there.

I spent a few days trying to get Vanderbilt's vice provost for university enrollment affairs, Douglas L. Christiansen, to speak with me and answer these questions more clearly and in more detail, but I couldn't. A university spokeswoman sent me some general information on his behalf. “We are committed to excellence at every level, from the quality of our faculty, programming, facilities and research laboratories to the services we provide to support the academic, emotional and social well-being of our students,” the statement said.

In anticipation of the lack of a substantive answer, I took part in a group information event for around 125 prospective students and asked questions there. The senior admissions officer who answered the question refused to answer. I had never seen this before and have attended these sessions at dozens of schools over the years.

But why should a player in a competitive market really answer this question if the person doesn't necessarily have to? Without publicly available, industry-wide quantitative data on quality—satisfaction scores, customer satisfaction, learning metrics, return on friendships, strength of career networks—list price alone serves as a signal of excellence for at least some buyers.

And thousands of applicants respond to the signal each year by voluntarily committing to pay list price, even if the school rejects the vast majority of applicants. Or perhaps they volunteer precisely because Vanderbilt and similar schools reject the vast majority of applicants.

So a list price of $100,000 is not our top priority. The spectacle of wealthy people freely purchasing luxury services is nothing new, although it is an entirely worthy subject of scrutiny (and a phenomenon little studied by scientists themselves, ahem).

Then what's a problem? Brent Joseph Evans, an associate professor of public policy and higher education in Vanderbilt's College of Education and Human Development, began his career as an admissions officer at the University of Virginia. There he sold the facility to boarders in New England and teenagers in the Appalachian foothills.

The former group could pay $100,000 a year, even though many of them don't even get into the Vanderbilts of the world. They will surely find their way somewhere.

But this latter group? Professor Evans is worried about her access to school at all.

“We should care about whether they get into a public university system at low cost and find a well-paying career that allows them to stay in the middle class,” he said. “I do think that tensions over what elite colleges are doing sometimes distract us from what we should care about as a society.”