Breadcrumb Trail Links

Indeed, in a year when supply emerged as the main concern, urban housing starts declined

Released on January 20, 2023 • 4 minutes read

The shortage of construction workers is expected to worsen as more people retire than enter the sector. Photo by PATRICK DOYLE /Reuters

The shortage of construction workers is expected to worsen as more people retire than enter the sector. Photo by PATRICK DOYLE /Reuters

content of the article

There is a growing consensus that a lack of supply is the main reason for Canada’s housing affordability problems. But if the 2022 housing start dates are any indication, doing something about it will be a challenge.

advertising 2

This ad has not yet loaded, but your article continues below.

content of the article

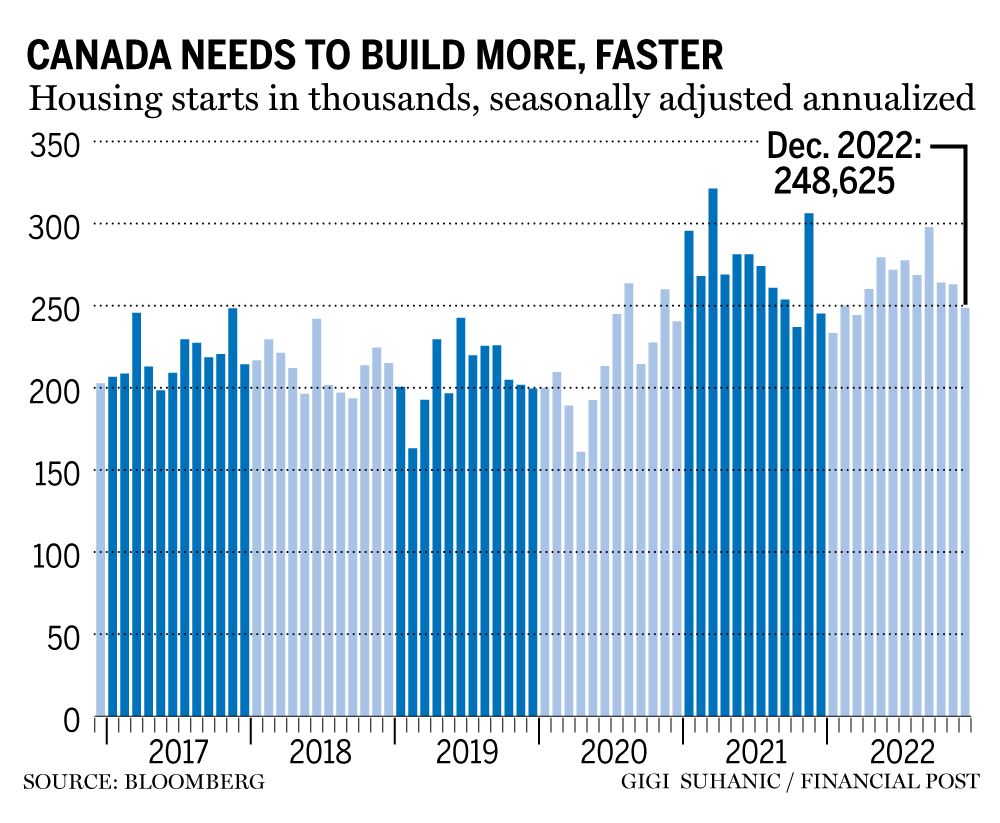

Figures released Jan. 17 by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) showed that city housing starts actually declined year-on-year in 2022, falling by just over a percent to 240,590 units.

Financial Post top stories

By clicking the subscribe button, you agree to receive the above newsletter from Postmedia Network Inc. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link at the bottom of our emails or any newsletter. Postmedia Network Inc | 365 Bloor Street East, Toronto, Ontario, M4W 3L4 | 416-383-2300

Thanks for registering!

content of the article

Although housing starts recorded by the CMHC remain at elevated levels compared to recent years, they are far from the levels needed to even mitigate the shortage that the national housing agency identified in June when it 5 million additional new housing units were needed by 2030 to improve affordability. That would be more than a doubling of the current tempo. Even the more modest increases of 30 to 50 percent that the CMHC later found that workers in some provinces could, at best, endure seems a long way off.

advertising 3

This ad has not yet loaded, but your article continues below.

content of the article

Many economists and property experts are warning that there are no quick fixes on the supply front and things could get worse.

“Houses take a long time to build and there’s a long lead time before shovels go in the ground,” Ted Kesik, a professor of civil engineering at the University of Toronto, said in an email. “Significant production increases take years, which is why so many people worry about the housing crisis and that it could actually get a lot worse before it gets better.”

That’s not to say governments aren’t trying.

The federal government has committed $78.5 billion to build more, while provincial governments are setting up housing affordability working groups to implement new recommendations, such as: B. the abolition of restricted zones.

advertising 4

This ad has not yet loaded, but your article continues below.

content of the article

“Restore Affordability”

Recently, Ontario’s Ford government opened up 7,400 acres of the Green Belt (a natural area north of Toronto) for development – a move that sparked a political backlash from conservationists.

Even with additional funding, improved zoning and new land, the labor force required for construction has dwindled in recent years, making it a limiting factor for any ambitious growth plans.

“Unlike some other industries, the construction industry has a firm capacity to build more homes and is losing many of its older and more experienced workers who are retiring,” Kesik said. “There aren’t enough new hires entering the workforce to make up for the attrition, and so the workforce is a key factor.”

advertising 5

This ad has not yet loaded, but your article continues below.

content of the article

Bill Ferreira, executive director of BuildForce Canada, echoed concerns about the workforce, noting that the federal government is making efforts to encourage skilled jobs, but the environment is still challenging.

“The latest census data indicates that 20 percent of Canada’s population is between the ages of 50 and 64. And only 16 percent are under 50. So if we start counting for the next 15 years, we know more people will leave the labor market to retire than enter the labor market,” Ferreira said.

The scale of the challenge is frightening. CMHC chief economist Bob Dugan said launches in 2021 and 2022 were well above the pace of the previous decade, but needed to grow much further from there.

advertising 6

This ad has not yet loaded, but your article continues below.

content of the article

“The average pace of (all) housing starts (from) around 2010 through 2019 was about 201,000 housing starts per year,” Dugan said in an interview. “Even the number of urban launches we saw in December is way ahead of that pace. But the main problem is that we need a lot more in terms of supply… If we want to make the housing markets affordable again, we need to find a way to double the pace of construction.”

Tight labor market

That means government programs must find a way to incentivize higher levels of construction despite labor constraints.

“The job market is very tight, but what we need to do is be more innovative in the way we build houses,” Dugan said. “We need to find new approaches that can use the existing labor pool more productively to build more homes. We need to find a way to build more efficiently. That’s the key.”

advertising 7

This ad has not yet loaded, but your article continues below.

content of the article

Robert Hogue, deputy chief economist at the Royal Bank of Canada, says it’s still unclear how much capacity constraints will ease over time.

“Even if all levels of government remove regulatory barriers to building more housing, ultimately construction may still be hampered by capacity constraints and particularly labor shortages,” Hogue said.

In October, the federal government announced its pledge to let in 1.2 million immigrants between 2021 and 2023, who could provide much-needed support for the construction industry. However, they also need a place to stay.

-

The average rent increased by 10.9% in 2022, the report shows

-

The pace of housing starts slowed in December and ended flat compared to 2021

-

Canada’s home prices will fall nearly 6% this year, CREA forecasts

advertising 8

This ad has not yet loaded, but your article continues below.

content of the article

Kesik predicts that if history repeats itself, efforts to create more housing will yield results, but will take time to have an impact.

“My parents were immigrants and they told me that after World War II there was a terrible housing shortage and they had to live in very poor housing that was infested with bugs and vermin,” Kesik said. “Eventually things got better, but it took almost a decade.”

Given today’s construction reality, even that kind of timeline could be ambitious, he said.

“Back then, in the 1950s, houses were less than half the size they are now, with few features, and so they were affordable and built very quickly. We don’t build that many single-family homes compared to condos these days, and these projects have been slow to deliver our much-needed homes.”

• Email: shcampbell@postmedia.com

Share this article on your social network

Remarks

Postmedia strives to maintain a vibrant but civilized forum for discussion and encourages all readers to share their views on our articles. Comments may take up to an hour to be moderated before they appear on the site. We ask that you keep your comments relevant and respectful. We’ve turned on email notifications – you’ll now receive an email when you get a reply to your comment, there’s an update on a comment thread you follow, or when a user you follow comments follows. For more information and details on how to customize your email settings, see our Community Guidelines.